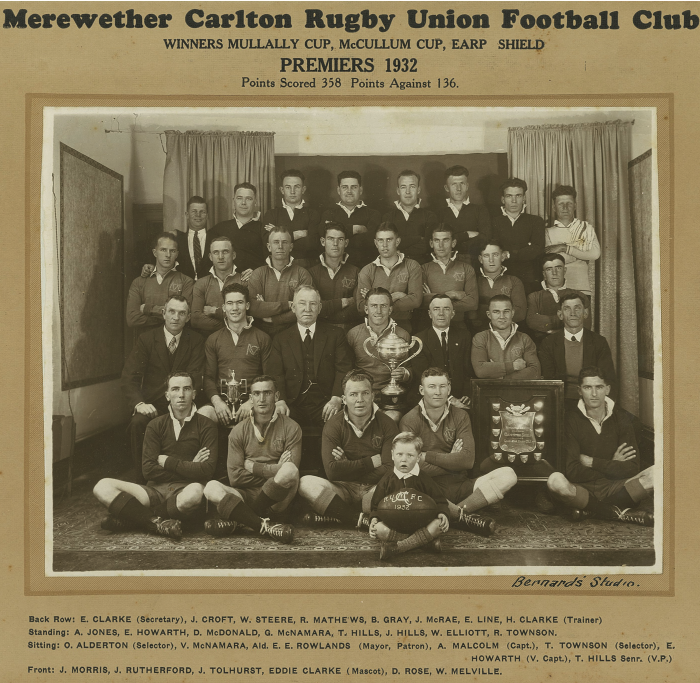

JACK CROFT 2/15 Field Regiment

Jack Croft is a Merewether Carlton “original” having played in the Club’s very first game on 5th July 1930 following the then recent amalgamation of the Merewether (previously Cooks Hill Surf Club RUFC) and Carlton Clubs.

With a previous history in Rugby League, Jack played Rugby for the Carlton Club in 1928,29 and in the first NRU Competition of 1930. He went on to play 31 games, all in 1st Grade, for Merewether Carlton from 1930-32.

Jack Croft was a member of the Club’s first 1st grade Premiership in 1932.

Following his enlistment in 1940, Jack’s 2/15 Field Regiment was posted to Malaya in August 1941, by which time he had been made up to Serjeant.

(Jack is centre front in the above photo)

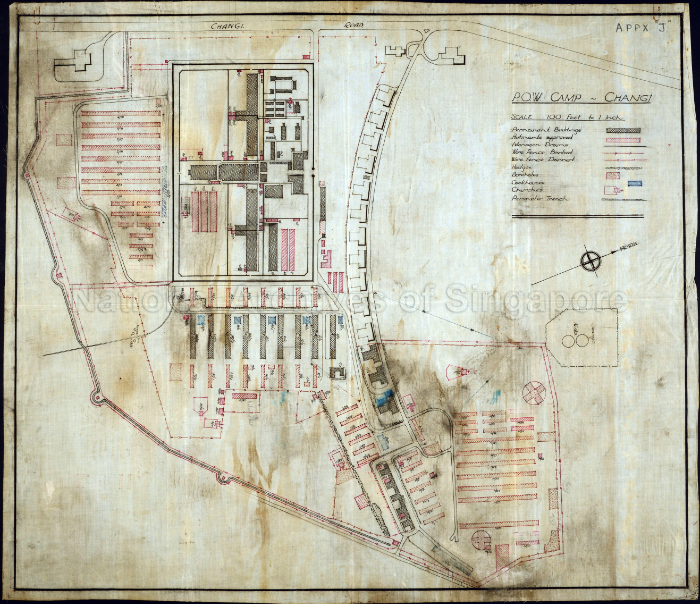

From mid-January 1942 Jack’s unit was engaged in a fighting withdrawal down the Malayan Peninsula and across the Causeway to Singapore Island until the Allied leadership surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February. Two days later, the regiment began moving from Tanglin Golf Course to Selerang Barracks, Changi, into Japanese capture.

Changi PoW Camp comprised the grounds and barracks of the British Military and Naval facility on Singapore.

Jack had been keeping a Diary which is now held at the Australian War Memorial. The following is an extract from the Diary’s Preface, written by Jack’s son.

This typescript was transcribed with considerable difficulty by Sally Nicol from a variety of manuscript sources. The diary consists of a Battle Diary recording action until the Capitulation in February 1942, and then an account of daily life in Changi Gaol and its surrounding work camps until Liberation in September 1945. Early parts of the diary were written clearly on the back side of commercial invoice forms, later entries on various paper scraps, including the margins of books from the Changi Library. As far as I know, the diary was a daily record (except when Jack was ill) and written at the time. It was kept in secure places and under considerable secrecy. Some of the entries were impossible to decipher 60 years later, and some have been lost. I owe a great debt to Sally Nicol for the effort and dedication she put into the transcription over many months. By her efforts my father’s words and life have come into being. It has been a very moving experience for me reading this diary, and I hope it will be for any other reader, who, while not having the benefit of a close familial relation with the diary-keeper, will nevertheless have an insight into what so many men and women suffered in World War Two.

[Julian Croft]

A reading of Jack’s diary will lead to an undoing of the generally held understanding of the Australian servicemen’s experience in Changi.

It becomes apparent to the reader that Jack’s spirit diminishes as his internment goes on and on and on. Apart from his worry about, and lack of news of, his wife, son, and family there is the constant presence of disease and infection from dysentery, beri beri, malaria, scabies, and a variety of other forms of sickness. There are recurring PoW deaths and burials, boredom and being required daily to deal with cockroaches and a variety of bug infestations on a grand scale. He is always malnourished, going from a solid 14 stone weight to under nine.

But a constant theme through the diary is the failure of their leadership and worse – the theft and black-market operations involving food Red Cross parcels, and other essentials intended for all PoW’s. Jack writes often of those PoW’s engaged in the management of the camp food and supplies, the cooks, hospital orderlies, and officers stealing and generally benefiting themselves.

A link to download Jack’s diary is provided at the end of this article.

A chat with Jack’s son, Julian, will give an understanding of Jack being a bloke who liked a drink, a fag and a punt, and as someone not prepared to back off as evidenced by this extract from his Changi diary.

15 June 1942. “Had a bit of a scrap with a cove, pretty good fighter too. It went for about 5 minutes and was then stopped. I don’t think I disgraced myself. I received a split lip and presented him with a disfigured nose, split his eyebrow and gave him a beautiful black eye. He is a pretty powerful cove, not much taller than myself but about a stone and half heavier and 13 years younger.”

Jack’s boxing experience, referred to in the following background provided by son Julian, may have come in handy.

Jack Croft

(for Anzac Day 2023, Mitchell Park, Merewether-Carlton RUFC – by Julian Croft)

Jack Croft — Who was he? What was he like?

Even though I’m his son, I really can’t tell you much from my direct experience. I was born at the end of May 1941, Jack went with the 8th Division AIF to Malaya in September 1941, and didn’t return to Australia until November 1945. He died in Merewether three years later in November 1948. That’s the bare bones. However, years later, I read many of the letters from his friends to my mother after he died, and one of the recurring phrases in them was ‘he was a man’s man.’ You might get some impression of what they meant when you read the diary (almost 400,000 words) that he kept during active service in Malaya and imprisonment in Changi.

Who he was is the easy part.

He was an athlete with local gold medals in Boxing and Rugby League, and, of course, in the premiership Merewether-Carlton team of 1932. In that he followed his father Clarrie, with whom he played in the same first-grade Tighes Hill Rugby League side in 1921. Clarrie also had medals from the Royal Humane Society for rescuing people from drowning in Newcastle Harbour and Newcastle Beach.

Jack was born in 1904 in Union Street, Tighes Hill. The family had lived there for many years. The family was active in politics. His grandfather James Thomas was on the Wickham Council and his brother, Uncle Jack, was in the second draft for the Australian Senate in 1903, as a Labour Senator for Western Australia. According to family tradition, Grandfather James had had a colourful career as a crewman for Bully Hayes (American pirate and black-birder), and had fought with the NSW Contingent in the Maori Wars, for which he was given a land grant in New Zealand. Later in life he set up a business supplying water to shipping in Newcastle Harbour, J. Croft and Son, which was active from the 1890s until the 1960s. In fact, the family had been in Newcastle since 1818 when James Thomas’ father, Jack’s great-grandfather, another James, was appointed Convict Overseer of the Newcastle Gaol, which he ran until the 1840s. He was a Waterloo veteran with the Waterloo Medal and had been transported for Highway Robbery in 1817.

Jack left Newcastle Collegiate School at 16 and joined the Hunter District Water Board as a Clerk, and worked there until he enlisted in 1940. After the War, he took over J. Croft & Son. His father was on the committee of the Newcastle Jockey Club, and Jack had interests in various horses before the War. The family had a very strong tradition of active involvement in sporting and community affairs: the Rocket Brigade, the Volunteer Fire Brigade, Surf Life Saving. That was the milieu Jack grew up in. In the late 1920s the family moved from Tighes Hill to Nesca Parade in Cook’s Hill. So, it’s not surprising Jack took up with Carlton Rugby Club with its original associations with employees of Arnott’s Biscuits factory in Cooks Hill and Cooks Hill High School ex-students and, later, Merewether-Carlton.

Jack didn’t marry until he was 36, which was probably unusual at that time. There seem to have been several girlfriends over the years, but I don’t have any knowledge of them. His relationship with my mother started in the mid 1930s when she was in her early twenties and he was ten years older. The only thing I know about their courtship was that she refused to marry him until he paid off his gambling debts (the horses!), which he dutifully did, and they were married in June 1940.

Her letters to Jack in the first years of their marriage when he was training in the Army are quite delightful and joyful—none of the foreboding you would think given the circumstances of the time. They are now in the National Library in Canberra. For two-and-a-half years after the fall of Singapore I believe she didn’t know whether Jack was dead or alive. One can only imagine the distress this caused to her and Jack’s family in Nesca Parade. Being a wife for a few months, then a mother, and a possible widow all within less than two years would test the mettle of anyone, but she coped, and did her best to welcome home the man she married five years before, but now barely knew. It was a common story of the time.

What we he like?

As to Jack’s temperament, you can judge that from his diary. He had a strong moral sense and was quick to respond to anything he thought was ‘low’ behaviour, often with force, if required. He was contemptuous of those who used positions of power in selfish or dishonourable ways, and, complementary to that, keen to help the disadvantaged, as we can see by his gardening to supply ‘greens’ to the prison hospital for beri-beri patients. ‘Greens’ which were often stolen by other soldiers (or even officers).

My memories of him in the immediate post-War period when I was four to seven are hazy, but I remember a dreamy presence, though a quick temper, and a willingness to ‘do the right thing’ by a boy who really didn’t know what he was supposed to do, or be, to this stranger who was suddenly in the family. It was a familiar experience for many post-War children. We now are more aware that the effects of the battlefield or prison-life are not left on the battlefield or prison, but persist through years in families — all the way from Waterloo through Botany Bay to Changi.

Julian Croft,

Laurieton,

April 2023

FURTHER READING

- Incase you missed our story last week introducing Jack Croft and Aub Jones you can view it here.

- Jack’s Diary can be viewed/downloaded here

- Australian War Memorial – Changi

- Anzac Portal – Australian Prisoners of War

Social NewsNews and information

Merewether Carlton Rugby Club

4 days ago

Photo

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linked In Share by Email

5 days ago

To read the full story head to merewethercarlton.com.au/anzac-day-2024-a-tribute-to-dr-idris-the-doc-morgan/ ... See MoreSee Less

Photo

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on Linked In Share by Email

Merewether Carlton Highlights @carltonrugby

@carltonrugby Rugby Union Club

merewethercarlton

Official account of Merewether Carlton Rugby Union Club 🟢

Est. 1930

#bleedgreen